Posts in Category: Museums

WW2 Photo Appeal

One of the places I am most looking forward to visiting one of the days is the Imperial War Museum in Duxford. It’s quite ridiculous that I spend most of my holidays in Cambridge and have somehow never managed to make it there, but I do tend to use my school holidays as time to sit and let my brain stop whirling. But yes…someday soon.

I was intrigued, therefore, when I saw an article about the American Air Museum in Britain was asking for people to come forward and identify local people who worked there during WW2. There is an archive of some 5,000 photographs and, as time passes, the chances of identifying the people in them grows smaller. I really hope this appeal travels far and that the museum’s curators can find and identify many of the people in the photographs, and possibly share their findings with the public. That is one exhibit I would be fascinated to visit.

War and Remembrance

On Thursday, as well as fitting in some shopping and wandering through town, I stopped in at the Fitzwilliam Museum for a look at their new exhibit, La Grande Guerre. It featured a collection of lithographs and woodcuts from the Great War, donated by the daughter of Cambridge’s own Gwen Ravarat, and arranged chronologically so that the viewer can see the change in tone as the war progresses. I found the exhibit very moving, and the thoughtful curation of the prints allowed the viewer to see the progression from complete nationalistic control of this military propaganda to letting in just the tiniest slips about the realities of the battles.

I was slightly surprised to see how the artists included quite a few images of the various cultural groups who fought in the war. There were the ‘Turks’, the Senegalese, Tunisian and Algerian troops who fought with the French, and ‘les Hindous’, the 1.5 million Indian soldiers who fought alongside the British. In fact, I am more than a little in love with that print, and brought home a small copy.

I was slightly surprised to see how the artists included quite a few images of the various cultural groups who fought in the war. There were the ‘Turks’, the Senegalese, Tunisian and Algerian troops who fought with the French, and ‘les Hindous’, the 1.5 million Indian soldiers who fought alongside the British. In fact, I am more than a little in love with that print, and brought home a small copy.

I lingered so long over the exhibit that I didn’t get a chance to have a wander through the rest of the museum, but I’ll be back. In one of those delightful jumps in time, I moved from the First World War to the Second, meeting Paul for drinks at The Eagle.

I’ve been meaning to visit The Eagle since I first heard about it — and it’s well worth hearing about! It was here where Watson and Crick celebrated the discovery of the structure of DNA (or, at least, where they drank to this discovery). Of more personal note, it’s also where the American soldiers stationed in Cambridge during WW2 used to drink. Fortunately for us, they left behind a bit of the past. In grand American tradition, the soldiers graffitied the ceiling of one of the rooms with their serial numbers and other messages. While the bar obviously caters to American tourists (odd hearing so many American accents in one room), it still has the feeling of a local pub, with students and faculty enjoying a quick after-work drink. We were lucky enough to squeeze into a booth in the back room, but there’s also a beautiful front room with glowing stove that must be gorgeous on a rainy winter’s day, and a few tables outside for a beer under the sun. Will definitely be heading back soon.

Scott Polar Museum

One of the many reasons I love the essayist Anne Fadiman’s writings is that she is an unabashed lover of all things explorer, especially the Antarctic expeditions. It’s impossible not to be drawn to someone who writes so beautifully of their bravery and the poignant humour in their failure.

“Americans admire success. Englishmen admire heroic failure. Given a choice – at least in my reading – I’m un-American enough to take quixotry over efficiency any day. I have always found the twilight-of-an-empire aspect of the Victorian age inexpressibly poignant, and no one could be more Victorian than the brave, earnest, optimistic, self-sacrificing, patriotic, honorable, high-minded, and utterly inept men who left their names all over the maps of the Arctic and Antarctic, yet failed to navigate the Northwest Passage and lost the race to both Pole. Who but an Englishman, Lieutenant Edward Parry, would have decided, on reaching western Greenland, to wave a flag painted with an olive branch in order to ensure a peaceful first encounter with the polar Eskimos, who not only had never seen an olive branch but had never seen a tree? Who but an Englishman, the legendary Sir John Franklin, could have managed to die of starvation and scurvy along with all 129 of his men in a region of the Canadian Arctic whose game had supported an Eskimo colony for centuries? When the corpses of some of Franklin’s officers and crew were later discovered, miles from their ships, the men were found to have left behind their guns but to have lugged such essentials as monogrammed silver cutlery, a backgammon board, a cigar case, a clothes brush, a tin of button polish, and a copy of The Vicar of Wakefield. These men may have been incompetent bunglers, but, by god, they were gentlemen.” – Ex Libris

One of the more intriguing museums in Cambridge is the Scott Polar Research Institute. Founded both as a memorial to Scott after his last ill-fated voyage and as an institute to continue his scientific goals, it is now a museum, research facility, laboratories, and home to the Shackleton Memorial Library. It is a gem of a museum with some very important, very moving collections. There are last letters penned to wives and parents, scientific and photographic tools used during the expeditions, and even birds brought back from more successful ventures.

These baby emperor chicks are a touching reminder of the kind of birds and wildlife these men found and introduced to the Western world. They’re also just very sweet.

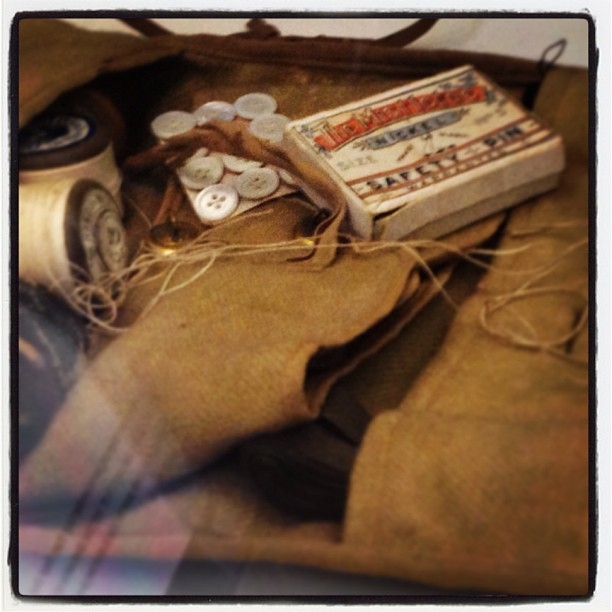

Even more than the letters home, what I found most moving was the collection of everyday items found after various lost expeditions. The goggles Scott wore, based on an Inuit design, to help protect him from the glare on the snow. The balaclava knitted by a member of the royal family for the expedition, demonstrating the excitement the whole country felt for these explorations. The huswife that was probably used every day, with the original needles and threads, and pockets to store other necessary items. It’s a comprehensive collection of the various explorations, but the museum also includes sections on the climate, native peoples, and future of these areas. It also has a smashing selection of books, which I carefully edged away from, but I’ll definitely be going back to see it again and to snap up biographies of these amazing men.

Laura Knight Exhibit

As well as hitting some of the more familiar tourist sites around Trafalgar Square while I had time to myself, I wanted to see some of the less permanent offers, so I headed for the Laura Knight exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. I’d seen posters around town and several people had already raved about how good it was, so I made my way there with just a short stop in Chinatown for coconut bubble tea. Do you see that…ice, ICE! I must go back soon for more, and to sample the truly amazeball-smelling dumplings being made as I slurped my drink.

Anyway, the exhibit was splendid. The portraits were compelling, there was enough space to have a really good look, and it was thoughtfully curated. I was familiar with Knight’s war work, but was surprised to discover that she had immersed herself in African-American culture in pre-civil rights Baltimore, and then with a Roma community in England. In fact, what emerged from the exhibit was Knight’s ability to see a whole picture, and the desire to paint reality in all its beauty and ugliness.

Even in her commissioned works, like this portrait of a dancer, she wasn’t content to just show the pretty picture, but quietly revealed the domestic landscape of the dancer, including the workers who helped make the beauty happen. Her portrait of the Nuremberg Trials was incredibly moving, showing both some of the main ‘characters’ in the trial and, in a break from reality, an impression of the blitzed city just beyond blending into the proceedings inside.

I had not realised before the exhibit that Knight had written an autobiography. Sadly, it seems to be from early in her career. I want to find a really thorough biography of this stimulating artist!

The Fitzwilliam Museum

Yesterday, after a leisurely morning (well, for me…Paul worked from home), we wandered in the direction of The Fitzwilliam Museum. I’d passed it several times when visiting before, and we’d once popped in just to have a quick peep, but this was my first time to really get a chance to look around. We started our museum tour with a visit to the cafe, a technique I can fully endorse.

The museum is vast, so promising myself several return visits to fully explore, we passed quickly through rooms of Madonnas and fat angels to get to the French and English galleries. No matter how many museums I visit, it’s always astonishing to find oneself surrounded by paintings, prints and sculptures and then being left to make sense of them. I wandered through the galleries, finding old favourites, adding new ones, and just enjoying my usual game of trying to understand about what the curators were thinking in the arrangement of the gallery.

I found this wall in the 20th century English art gallery most pleasing. Women reading, thinking, and spending time on their own in domestic settings…lovely.

And as an added bonus, outside or in, it’s a beautiful place to look up.

Recent Comments